|

Bay CrossingsNews

CAN THE BAY AREA PROVIDE THE SHIPBUILDING

AND REPAIR SERVICES NEEDED FOR A REGIONAL FERRY SYSTEM?

By Wes Starratt, P.E.

|

| The Bay Ship and Yacht

Company facility in Alameda with downtown Oakland in the background |

San Francisco Bay Area has a long and well-established tradition of shipbuilding

and ship repair. The City was founded as the major Pacific Coast port, and the

Bay Area remains in the forefront of world trade. Shipbuilding and ship repair

went hand-in-hand with the regionís function as a port.

The Gold Rush of 1849 quickened the need for Bay Area and

coastal transportation, and shipyards were established to turn out wooden sloops

and schooners to carry cargo and passengers. Naval ship repair facilities in the

Bay Area were given a high priority, and the Mare Island Navy Yard was

established for that purpose in 1854.

The need for mining machinery and heavy equipment prompted

the establishment of metalworking firms such as San Franciscoís famed Union

Iron Works. But, as the needs of the mining industry began to diminish, these

firms turned to other markets, such as steamboat engines and shipbuilding.

Wooden shipbuilding was to continue for a few more decades, largely in the

Oakland Estuary. But steel had entered the picture. The first steel ship was

launched in San Francisco in 1885 by Union Iron Works, which became the first

large modern shipyard on the Pacific Coast. The shipyard continues building and

repairing ships to this day under the name of San Francisco Drydock. .

World War I stimulated shipbuilding activity around the Bay,

with shipyards in San Francisco and along the Oakland Estuary turning out

military and cargo ships. From that time onward, Mare Island began building

large warships and heavy cruisers as well as destroyers and, in more recent

years, nuclear-powered submarines.

|

| Bay Ship works on a

historic sailing ship. Owner Bill Elliott got his start in the boat

building business as a wooden boat craftsperson. |

But, it took World War II, for the Bay Area to be transformed

into the largest shipbuilding center that the world had ever seen. In 1940, the

Navy purchased Hunterís Point dry docks from Bethlehem Steel Co., made it an

annex of Mare Island, and doubled its capacity with the addition of drydocks,

machine shops, and fabrication facilities. At the same time, facilities were

added and shipbuilding activities at Mare Island were dramatically increased.

In the once sleepy little town of Richmond, industrialist

Henry J. Kaiser transformed the bay shore into four shipyards employing 90,000

workers that built a total of 747 Liberty, Victory, and Naval ships on a

production-line basis. By warís end, the lights were burning round-the-clock

in Richmond as the production of ships from 27 shipways approached one every

other day.

Across the Bay, a similar transformation took place as

Sausalito became a major center of shipbuilding for the war effort. Taken

together, the Navyís Mare Island and Hunters Point yards, plus the four Kaiser

Shipyards in Richmond, the Bechtel yards in Sausalito, the Union Iron Works,

shipbuilders along the Oakland Estuary, and other yards, the Bay Area was the

center of worldwide shipbuilding during the war years.

|

| Two workboats sit in

Bay Shipís drydock while undergoing repair |

The achievement was so profound that it caused Winston

Churchill to write, "Without the supply columns of Liberty ships that

endlessly plowed the seas between American and England, the war would have been

lost." A substantial number of those ships were built right here in the Bay

Area.

But the glow didnít last for long. Within a few short

years, the yards in Richmond and Sausalito were history. By 1975, the Navy

closed its Hunters Point Yard, and finally, in a frenzy to close military bases,

Ship Yard Mare Island was closed a few years ago.

Today, what is left? The Union Iron Works, now San

Francisco Dry Dock, after more than a century of activity, is still engaged in

large-scale ship repair operations, and ship repair facilities for tugs,

ferries, tour boats, and smaller vessels exist around the bay.

The Bay Area, under the pressure of World War II, transformed

itself into the center of worldwide shipbuilding. Can the Bay Area do it again

on a much smaller scale for the regional high-speed ferry fleet that is needed

to relieve the areaís transportation gridlock?

San Francisco Bayís ferry system, as it was

There was a time when the bay itself was almost the only

medium for transportation in the area, and San Francisco was at the hub. Both

transcontinental railroad lines had reached the eastern shore of the Bay: the

Southern Pacific in Oakland, and the Santa Fe in Richmond. Passengers and

freight were transferred from trains to waiting ferries for the trip across the

bay. Even railroad cars were rolled onto barges and delivered to yards in San

Francisco.

|

| Old hulks off Hunterís

Point Shipyard in 1932. Then, as now, the shipyard had fallen into

disuse. Note the ferryboat Bay City. |

If you lived in the East Bay and worked in San Francisco, you

took one of the many SP or Key Route trains and transferred to the ferries. In

Marin and Sonoma counties, you took a train to Sausalito or Tiburon to catch a

ferry for the trip to work. Literally thousands of commuters passed through San

Franciscoís Ferry Building every day on their way to and from work.

Most of the ferries carried both passengers and vehicles. For

many years, the ferry was the only way to cross the bay, or even to cross the

Carquinez Straits, or get from Richmond to San Rafael, whether you were

commuting to work, delivering goods, or taking the family for a Sunday outing.

In the 1930ís came the bridges, and soon passengers and

vehicles began leaving the ferries for the much faster trip across the bay. It

didnít take long before ferry service on the bay ceased to exist. Ferries had

become not only an endangered species, but also a species that ceased to exist.

For some 30 years, there was no regular ferry service on the bay, and freeways

crowded with automobiles completely dominated local transportation. The old

single-steel-hull ferries were indeed too slow for the pace of modern life.

|

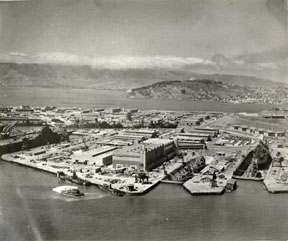

| Hunterís Point Naval

Shipyard in itís heyday; and aerial view taken in 1945 |

By the 1970s, the picture began to change dramatically when

ferry buffs began to realize that there was a way to attract passengers: give

them speed and comfort, and they will come!

Their persistence led to three technological breakthroughs

that completely revolutionized ferryboat design. It started when they began

asking specific questions such as,

Why not build ferries of a lighter material than heavy steel

plate?

At the same time, the aluminum industry was eying new markets

where the metalís lightweight and structural strength was a distinct

advantage, but where the difficulties encountered in welding the metal had been

a barrier. After years of effort, metallurgical engineers persisted, and

breakthrough-welding techniques were finally developed, ushering in a new

generation of ferries built of lightweight aluminum.

The second and third steps of the revolution in ferryboat

design had their roots in far off Sydney, Australia, where the locals retained a

fondness for ferries. They began asking

Why have a single-hull vessel? Why not have two or more

smaller hulls that would create less resistance as boats moved through water?

Why not use another means of propulsion than traditional

propellers? Why not water jets?

One by one, solutions were developed resulting in three

technological breakthroughs that set the stage was set for

|

| Hunterís Point Naval

Shipyard in itís heyday; and aerial view taken in 1945 |

The Dawn of the Age of High-Speed Ferries

In the Bay Area, the Golden Gate Bridge District, seeing the

pressure of mounting traffic congestion on the bridge, was the first to plunge

into the new era of commuter ferry service utilizing recently developed welding

techniques for fabricating aluminum hulls. Acting on a ferry transportation plan

developed by Philip F. Spaulding and Associates of Seattle, Washington, a

unique, single aluminum-hull vessel was designed. Working with Kaiser Engineers,

a terminal site was selected at a former barge-loading facility at Larkspur

Landing, and a ferry terminal was built. By 1976, the first 725-passenger

aluminum ferry was in operation, carrying passengers on a 45-minute run to the

Ferry Building. The venture proved to be so successful that two additional

ferries of similar design were added.

Next to enter and then dominate the Bay Area ferry scene were

the catamarans. These high-speed ferries took advantage not only of lightweight

aluminum, but also twin-hull design and water-jet propulsion systems. They can

attain speeds of 36 knots, while requiring a draft of only five feet (important

in the shallow waters of the bay), and providing a fast, comfortable ride. Red

& White Fleet placed the first of the catamaran ferries, the "Catamarin,"

in service between Tiburon in Marin County and the Ferry Building in 1985. What

had been a 40-minute run was reduced to only 20 minutes, giving passengers

scarcely time to gulp their coffee. The operation proved so successful that a

second catamaran was ordered.

The dawn of the "Age of High Speed Ferry Service"

had begun, and high-speed catamaran ferries began operating to Tiburon,

Vallejo, and Alameda/Oakland, as well as for tour and excursion service. At

Larkspur Landing, Golden Gate Ferries placed its first catamaran, the "Del

Norte," in operation, reducing the run to the Ferry Building to only 30

minutes. That service proved so successful that a second vessel has been

ordered. An additional catamaran is also on order for Alameda, with further

orders expected for Vallejo and possibly Richmond and Redwood City. Because of

the appeal of the fast, comfortable service provided by the high-speed

catamarans, the Bay of San Francisco is once again becoming a transportation

corridor. The number of regular ferries of all types operating on the bay has

increased from zero to more than a dozen.

|

| Early Hunterís Point

(date unknown) |

The Metropolitan Transportation Commission foresees an

increase of only five vessels in the immediate future, but the number could

increase dramatically, if the plan for "A Bay Area High-Speed Water Transit

System for the 21st

Century" is implemented in whole or in part by the recently formed San

Francisco Bay Area Water Transit Authority. That plan calls for 28 new ferry

terminals and 75 high-speed ferries.

All of the high-speed aluminum catamarans in operation in the

Bay Area have been built on Puget Sound in the State of Washington Ö most of

them by Nichols Bros. Boat Builders in Whidbey Island, Washington, under license

from International Catamarans, Ltd. (Incat) of Australia. A second firm, Dakota

Creek Industries of Anacortes, Washington, is building catamarans under license

from Advanced Multi-Hull Designs also of Australia.

In the Bay Area, the maintenance and repair of these ferries

is being done by local shipyards, with Golden Gate Ferries able to handle all

but major maintenance requiring dry docking.

As the number of aluminum catamarans operating in the Bay

Area increases, questions arise:

First, can these vessels be maintained and serviced by

existing local facilities, in view of the stringent requirements for aluminum

fabrication?

Secondly, can these vessels be built right here in the Bay

Area?

Specialized fabrication techniques

|

| Showing off the Navyís

630 ton crane, the worldís biggest: the caption boasts that, such is

the finesse of the crane, the operator is able to break the eggshell Ė

but not the yolk. |

It must be emphasized that a key factor in the building,

maintenance, and repair of these vessels is that they are made of aluminum.

Welding must be done in a dedicated covered environment, out of the wind and out

of the rain, uncontaminated by steel fabrication, and free of dust and moisture.

Welders must be specially trained and certified by the US Coast Guard. In Puget

Sound, the shipyards of both Nichols Bros. and Dakota Creek have been especially

designed for aluminum fabrication.

Ship Repair

In the Bay Area, almost all of the drydocking and major

repairs to aluminum-hulled ferries, including those of Golden Gate, Blue &

Gold, and Red & White fleets, has been done by Bay Ship & Yacht

in Alameda. The firm has trained and certified aluminum welders, developed an

expertise in aluminum fabrication, and established the necessary specialized

repair facilities. With these capabilities, the firm appears to have been the

only one bidding on the repair work and drydocking of the catamarans. Pacific

Maritime magazine, in its annual shipbuilding issue, lists Bay Ship &

Yacht with one drydock having a lift capacity of 2,800 tons, two outfitting

docks on the Oakland Estuary, two fabrication buildings and other shops. The

firm has recently added a second drydock of smaller capacity.

San Francisco Drydock has the capability of doing drydock

repairs for the new ferries, but may not be prepared to develop the necessary

expertise and dedicated facilities for aluminum fabrication. As the largest

active shipyard in the Bay Area, the firm is listed by Pacific Maritime

magazine as having two drydocks each with a lifting capacity of 60,000 tons, a

floating crane, craft shops and fabrication buildings, plus a recently acquired

dock from the Navy. Some other shipyards, including Nautical Engineering in

Oakland, are capable of providing ship repair services. Few offer expertise in

aluminum fabrication, but that expertise could be developed.

Shipbuilding

|

| The waning days of World

War II: look at all the ships waiting off Hunterís Point. |

San Francisco Drydock is currently focused on servicing

larger cargo, cruise, and Navy ships, but the yard is capable of building any

type of ship or ferry.

Bay Ship & Yacht has already taken the first step toward

developing the facilities necessary for building catamarans. At the former

Alameda Naval Air Station, the firm has leased several bays of the former

Corrosion Control Facility, which features advanced environmental controls and

is large enough to handle a Boeing 737. Adjacent are former seaplane launching

ramps. Together these facilities could provide the closed environment necessary

for building aluminum ferries. In addition, Bay Ship & Yacht has a license

from a third Australian firm to build catamarans.

Former Naval Shipyards at Hunters Point in San Francisco and

especially Mare Island in Vallejo offer facilities that could be utilized for

building high-speed ferries. Unfortunately, each of them has problems.

Hunters Point was closed in 1975, and very little has been

maintained since then. According to a representative of the US Navy,

"Berthing is in bad shape, and buildings are in bad shape. There are three

drydocks at Hunters Point: two of them have not been maintained for more than 15

years. It would take $3 to $4 million to restore them, including the missing

caissons for closing the docks. The third drydock is leased to Astoria Metals

Corp, which has a ship breaking contract with the Navy." So, there is only

an "outside potential" for utilizing this former shipyard.

|

| Crowds of workers

gather for an announcement at Hunterís Point, a poignant reminder of

what once was. |

Mare Island offers a far greater potential. Facilities

include four drydocks measuring up to 675 ft in length, 88 ft wide, and 35 ft

deep, 13 berths up to 600 feet in length, five piers up to 725 feet in length,

three shipways, and numerous buildings that could be used for fabricating ships.

These facilities are actively being leased by Lennar Mare Island, LLC.

According to one of the shipbuilders from Puget Sound,

"Mare Island would be the logical place to start looking for a shipbuilding

facility in the Bay Area, but it has problems, since it was a steel fabrication

facility, and aluminum fabrication can not be contaminated by steel from a

previous operation." According another Puget Sound shipbuilder, "Our

first choice for a shipyard in the Bay Area would be Mare Island."

Fortunately, the base has been closed for only a few years so

most facilities are in relatively good shape. The cranes are still working, but

pump houses may need upgrading. Probably the major problem is dredging, since

none has been done since the base was closed a few years ago. There is heavy

siltation in the estuary, and gates to the graving docks are blocked by at least

15 feet of silt.

|

| Mare Island and

vicinity from the air. |

Former Kaiser Shipyard No. 3 at Richmond might also serve as

a site for a shipyard to build catamarans. It has two deep-water finger piers,

and five deep-water graving docks, the largest being 750 ft long, 100 ft wide,

and 30 ft deep. Two of the graving docks have gates and the others would require

a caisson for closure. There is a nearby concrete structure dating from the

1940s that possibly could serve as a fabricating shop, but probably such a

facility would have to be built.

Who Would Operate a "New" Shipyard for Building the

Bay Areaís Catamarans? Bay Ship & Yacht undoubtedly would have an interest

in expanding its shipyard and acquiring additional facilities. As for the two

catamaran shipyards in Puget Sound: One responded, "Our firm would

have no problem establishing a facility to build and maintain catamarans in the

Bay Area if there is the business." The other was less interested, citing

high labor and housing costs.

To answer the basic questions posed earlier in this article.

|

| Mare Island drydocks,

thought to be the best bet for a renewed shipbuilding on the Bay. Their

future is uncertain. |

1. Ship repair facilities are adequate for maintaining the

current fleet of dozen or more ferries, but would need to be expanded to meet

the further needs.

2. Shipbuilding capabilities could be developed to meet the

needs of an expanded regional ferry system by utilizing facilities at San

Francisco Drydock, facilities leased to Bay Ship & Yacht at the former

Alameda Naval Air Station, and rehabilitating facilities at the former Mare

Island Naval Shipyard and Kaiserís Shipyard No. 3 in Richmond.

Yes, we can build and maintain our ferry fleet right in the Bay Area! |