Waterfront Highways and What to

Do With Them.

By Neal Kronley and Carter

Craft

As

the baseball playoffs begin, we here at Waterwire recall that

fateful World Series in October 1989 when an earthquake disrupted

play and brought down the Embarcadero Expressway in San Francisco.

One unlikely result of this tragedy was the formation of a new

waterfront park and promenade easily accessible to the city’s

downtown and surrounding neighborhoods. Long before this

tumultuous event, neighborhoods, planners, policy makers, and a

myriad of other parties were already awakening to the negative

consequences of building waterfront highways.

As

the baseball playoffs begin, we here at Waterwire recall that

fateful World Series in October 1989 when an earthquake disrupted

play and brought down the Embarcadero Expressway in San Francisco.

One unlikely result of this tragedy was the formation of a new

waterfront park and promenade easily accessible to the city’s

downtown and surrounding neighborhoods. Long before this

tumultuous event, neighborhoods, planners, policy makers, and a

myriad of other parties were already awakening to the negative

consequences of building waterfront highways.

It would be an injustice to

write this article without at least one mention of the man

responsible for encouraging a culture of infrastructure building

and improvements centered on the automobile. Robert Moses—both

the tyrannical and the heroic—believed that drivers should enjoy

a pleasant view during car outings and lined the waterfront with

highways for their benefit. There’s a great irony here that

Moses never drove himself anywhere, and yet the legacy of this

policy continues to be the isolation of countless citizens—locally,

nationally, and internationally—from their waterfront.

Neighborhood activists, citizens

seeking new parks and renewed waterfront access, and advocates for

transportation alternatives consistently agree on the need to

closely examine highway developments and improvements. Some

victories have been made in the New York and New Jersey region,

but the course remains an uphill struggle.

Among

the mad looping highways of the Bronx, the Sheridan is not the

most widely traveled. Only 2 miles long, the expressway travels

along the Bronx River to connect the Cross Bronx and Bruckner

Expressways. The development of nearby Hunts Point as an

industrial center has resulted in an increase of truck traffic in

this Bronx neighborhood. Responding to this situation, NYS DOT has

proposed a new exit from the Sheridan that would increase traffic

and, to many in the neighborhood, forever isolate this neighborhood

from its waterfront. Joan Byron, an architect with the Pratt

Institute for Community and Environmental Development, is working

with a broad coalition of neighborhood groups in the South Bronx

to stop the proposed development. Ms. Byron stated that “After

50 years of the Interstate Highway System, we have to question if

it makes sense.”

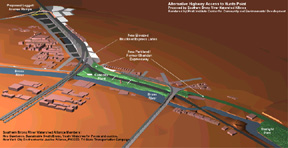

As an alternative to the NYS DOT

proposal, a number of organizations that comprise the Southern

Bronx River Watershed Alliance—Nos Quedamos, The Point,

Sustainable South Bronx, Youth Ministries for Peace and Justice,

The New York City Environmental Justice Alliance, Tri -State

Transportation Campaign, and PICCED—have proposed closing the

Sheridan to vehicular traffic and developing a 28-acre waterfront

park. Although this park would complement the exciting projects

already underway on the Bronx River, the Governor’s office has

refused to direct NYS DOT to study the community plan. The

community groups hope to make progress at a neighborhood meeting

with state officials on October 10.

Like

many highways in our region, New Jersey’s Route 21 abuts a

riverfront, the Passaic River. Recent developments on the New

Jersey side of the Hudson River have been both innovative and

encouraging for residents, visitors, and urbanists alike: a new

state park is being created in Newark, light rail transit projects

are enhancing linkages between communities, and the renowned NJ

Performing Arts Center has struck a new cultural tone for Newark.

Despite these forward thinking actions, NJ DOT is currently going

forward with plans to expand the highway closer to the waterfront—a

move that will further distance local communities from their

waterfront. NJ DOT’s response to the need for improved

waterfront access is to build an access plaza over the highway, a

move that leaves activists such as Janine Bauer of the Tri-State

Transportation Campaign unfulfilled. Ms. Bauer believes that “NJ

DOT sees the waterfront as a traffic corridor.” A claim that is

difficult to refute given the agency’s current development

plans. Such planning is distant from the careful work of planners

and architects to enhance the rich culture of Newark’s “Ironbound

Community” by providing better access to the waterfront next to

busy Raymond Avenue.

Like

many highways in our region, New Jersey’s Route 21 abuts a

riverfront, the Passaic River. Recent developments on the New

Jersey side of the Hudson River have been both innovative and

encouraging for residents, visitors, and urbanists alike: a new

state park is being created in Newark, light rail transit projects

are enhancing linkages between communities, and the renowned NJ

Performing Arts Center has struck a new cultural tone for Newark.

Despite these forward thinking actions, NJ DOT is currently going

forward with plans to expand the highway closer to the waterfront—a

move that will further distance local communities from their

waterfront. NJ DOT’s response to the need for improved

waterfront access is to build an access plaza over the highway, a

move that leaves activists such as Janine Bauer of the Tri-State

Transportation Campaign unfulfilled. Ms. Bauer believes that “NJ

DOT sees the waterfront as a traffic corridor.” A claim that is

difficult to refute given the agency’s current development

plans. Such planning is distant from the careful work of planners

and architects to enhance the rich culture of Newark’s “Ironbound

Community” by providing better access to the waterfront next to

busy Raymond Avenue.

Later this month, the NYC Parks

Department will officially open a new park between 135th and 139th

Streets along the Harlem River in Manhattan. This new parkland is

the first phase of the Harlem River Park, a much desired

waterfront promenade not unlike those in Brooklyn Heights or

Hoboken, New Jersey, which will eventually extend to 145th Street.

Building a park between the

waterfront and the bustling Harlem River Drive comes with a number

of concerns for residents and community activists: protective

fencing must dissuade people from entering the highway but

encourage people to use the park, access to the water itself must

be developed, and “amenities” such as restrooms should be

provided if residents are to fully utilize the space.

Complementing these arduous but navigable boundaries, the NYC DOT

plans to rebuild or improve the condition of all of the Harlem

River bridges and use a stretch of riverfront between 131st and

123rd Streets as a staging area. NYC DOT will give the staging

area to the Parks Department after the completion of its

construction projects, but this will not occur until 2012. Tom

Lunke, Director of Planning for the Harlem CDC, explains the park’s

predicament, “NYC DOT wants no public access through the staging

area although there are different stages of construction.” Mr.

Lunke hopes a compromise will be made that allows the public to

use the riverfront safely during the construction process. As MWA

has pointed out in numerous meetings, construction of the Hudson

River Park/Route 9A project did include an interim pathway that

was installed beside the staging area and allowed for continuous

access. “What worked in the Village would work in Harlem, too,”

says MWA’s Carter Craft.

The NY/NJ region is linked by

the waterfront yet many people fail to notice the beauty and open

spaces along those corridors because they are zooming past or over

on highway. As the preceding examples indicate, there is an

entrenched culture of building and expanding expressways,

highways, and parkways next to the waterfront. Although it is

unlikely that we will part with highways and automobiles in the

near future, a dramatic shift in policy is not entirely unlikely.

The NY/NJ region has the capacity for and a cultural disposition

towards the use of more mass transit. MWA encourages local

community groups to advocate for smart uses of the regions

waterfront for pedestrian, bicycle, and waterborne transit