History on the Half Shell

Susan Pultz Williams

Next

time you lift a finely-fluted oyster shell to your lips and

slurp down the plump cold meat that tastes something like

the sea on a fresh clear day, consider this: you’re not just

eating a rich appetizer—you’re taking part in a timeless

dining ritual. You’re enjoying what native Californians

enjoyed in ancient times, what the gold miners prized after

a hard days work, what Jack London wrote stories about, and

what food connoisseurs in California and around the world

continue to crave. Passion for oysters is as old as the

hills surrounding San Francisco and Tomales Bays, hills that

have seen oysters come and go for thousands of years.

Next

time you lift a finely-fluted oyster shell to your lips and

slurp down the plump cold meat that tastes something like

the sea on a fresh clear day, consider this: you’re not just

eating a rich appetizer—you’re taking part in a timeless

dining ritual. You’re enjoying what native Californians

enjoyed in ancient times, what the gold miners prized after

a hard days work, what Jack London wrote stories about, and

what food connoisseurs in California and around the world

continue to crave. Passion for oysters is as old as the

hills surrounding San Francisco and Tomales Bays, hills that

have seen oysters come and go for thousands of years.

In prehistoric times, oysters thrived in

the Bay and were a diet staple of the Ohlone and Coast Miwok,

who lived in small villages beside the Bay’s creeks,

streams, and tidal wetlands. The mounds of shells that they

left behind, mostly oyster, mussel, and bentnose clam

shells, provide evidence that these native Californians

enjoyed an abundant shellfish population for many millennia.

Seventeenth-century Spanish explorers found shell mounds,

also called “middens,” as long as football fields and as

tall as 2- or 3-story buildings. Studies of the middens and

of ancient shell reefs long buried under Bay sediment

suggest that the oyster population peaked more than 2,000

years ago.

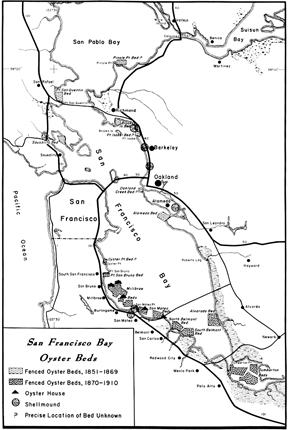

|

| Map of Bay

Area oyster beds 1851-1910. Illustration from

The California Oyster Industry, by Elinore M.

Barrett, California Department of Fish and Game

Fish Bulletin No. 123, courtesy Maritime Museum

Porter Library. |

We don’t know how the Bay’s native

oysters, Ostrea lurida, fared after that, but we do know

they were rediscovered by immigrants drawn to the Bay Area

by the Gold Rush. In the early Gold Rush days, miners paid

$20 a plate for Bay oysters, but were soon passing them up

in favor of John Stillwell Morgan’s imports from Shoalwater

Bay (now Willapa Bay) in Washington State. Called Olympias,

or Olys, the imports were the same species, but larger,

tastier, and more abundant. Soon oystermen began to store

and grow Olys in artificial beds along Sausalito’s

shoreline. Underwater fences kept out aquatic predators, but

could not hold back the tons of silt and mud washed down to

the Bay by hydraulic mining operations in the Sierra Nevada.

To avoid the silt, Morgan and other oystermen moved their

beds to Millbrae and the South Bay.

Then, after the transcontinental railroad was complete in

1869, oystermen began shipping East Coast oysters in from

New York. Packed in wooden barrels with plenty of ice, the

dime-sized Crassostrea virginica arrived at the Bay to be

fattened up in the artificial beds, and soon became more

popular than the Olys. Demand for the eastern “sea fruit”

grew and reached a peak in the ’90s when more than 250 train

car loads of oyster seed were shipped in and 2.7 million

pounds of mature oysters were harvested.

| Hog Island Oyster

Company If you like

half-shell oysters—raw, briney, and ice-cold,

you’ll want to try Hog Island Oysters from

Tomales Bay. Each year, Hog Island

aquaculturalists lift more than three million

plump, sea-sweet oysters with beautifully fluted

shells, from the pristine waters of Tomales Bay.

Oysters thrive in these waters, where

temperatures stay cool all year long, healthy

phytoplankton provide an abundant food supply,

and fresh water from springs and creeks mix with

salt water from the ocean. Hog Island received

the “Award of Excellence for Animal Husbandry”

from the American Institute of Food & Wine and

“The Best American Oyster” award from the San

Francisco Chronicle.

Hog Island proprietors Michael

Watchorn and John Finger started their company

in 1982 in a small, historic west Marin village

called Marshall, which once was a commercial

fishing town and a stop on the rail line that

moved seafood along the California coast.

Enjoying the history, they bought the

century-old Marshall General Store to house

their business, but mostly they were drawn to

Tomales Bay and its prime conditions for oyster

cultivation.

It took Watchorn and Finger

years to perfect their oysters; they modified

the labor-intensive, single-seed method of

farming until they got the results they wanted.

Now they use an 18-month-long process that

entails buying seedlings from hatcheries, then

planting the quarter-inch long seeds, called

spats, onto pieces of shell. Enclosed in mesh

cylinders, the spats grow to about one inch in

length, then are moved to mesh bags which are

tied to racks in the water. There the juveniles

stay until they grow to three to four inches and

are ready for harvesting. The mesh cylinder

stage is especially critical for producing an

attractive shell: as the cylinders roll with the

tide, the water thickens the shells and creates

the deep cup.

Hog Island follows meticulous

farming practices that ensure the health of

their oysters. A wet-storage system designed by

proprietor Terry Sawyer pumps sea water from the

Bay into tanks and sterilizes the water with

ultraviolet light. The chilled tanks hold a

fresh supply of live oysters when slight

declines in water quality require harvest

closures. Because of federal regulations and

regular testing, the oyster farming practices

are even safer than they need to be.

While you can find Hog Island

oysters at fine restaurants and seafood bars,

there’s nothing like a trip to Marshall to enjoy

oysters just pulled from the Bay. Hog Island

provides barbecue grills and picnic tables for

its customers, along with shucking gloves,

knives, instructions.

Visit the Hog Island Oyster Bar in San

Francisco’s Ferry Building Marketplace, Shop

#11-1. For information, call (415) 391-7117 or

e-mail hogislnd@svn.net. The mailing address is:

Hog island Oyster Company; P.O. Box 829,

Marshall, CA 94940. |

During these years, the heyday of

commercial oyster production in the Bay, hundreds of acres

of San Mateo County’s tidal mudflats were virtually paved

with oysters. Oyster pirates like Jack London, roving in

gangs, snuck into the commercial beds at night and stole

small boatloads of oysters. Then later, as London describes

in his short story from 1905, “A Raid on the Oyster

Pirates,” he joined the side of the law and helped bust the

poachers.

Around the turn of the

century, the Bay-grown eastern oysters began to fail, the

victims of raw sewage and industrial pollution; they were

blamed for several typhoid outbreaks. As production dwindled

and public suspicion mounted, oystermen moved their beds to

other west coast bays. Untouched by industrial

contamination, Tomales Bay, a narrow, 22-mile-long inlet

located 50 miles northwest of San Francisco, became a

preferred oyster growing spot. Oyster production in San

Francisco Bay stopped completely by 1939, but continued to

expand in Tomales Bay, where the industry still thrives.

A few oyster companies have settled in

Tomales Bay, now a National Marine Sanctuary, because it

offers the clean, cold water, abundant phytoplankton blooms

and tidal action necessary for growing rich-tasting oysters

with beautiful shells. Among these aquaculturalists, the Hog

Island Oyster Company started up in 1982 and now sells more

than 3 million oysters each year to fine restaurants around

the country. Hog Island grows four types of oysters, all of

them imports: the Pacific (also known as the Japanese

oyster), Eastern, European, and Kumamoto. (See inset.)

But in San Francisco Bay, oysters are scarce.

Siltation and contaminants continue to threaten the native

Olympia oysters (Ostrea lurida), as well as the entire

ecosystem; the more than 200 invasive non-native species

living in the Bay include exotics that prey on oysters,

crowd them out or consume their food supplies.

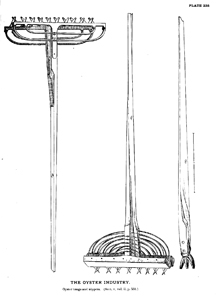

|

| Oyster

tongs and nippers, used to bring oysters up from

the water bed. Tomales Bay cultivators grow

oysters in nets instead. Fishery Industries of

the United States, United States Commission of

Fish and Fisheries, 1887, courtesy Maritime

Museum Porter Library. |

For the past few years, biologists have

been trying to figure out how to help oysters make a

comeback in the Bay. But what’s driving their interest is

not the commercial value of oysters: it’s that oyster reefs

would help boost biodiversity in the Bay by providing

habitat for small fish and invertebrates, which, in turn,

would be appetizing to larger fish and birds. It’s also that

these mollusks filter as much as 25 gallons of water a

day—either trapping sediment and pollutants in their bodies

or forming them into packets which they discharge onto the

bottom—meaning that a substantial oyster population could

improve the Bay’s water quality.

Restoration projects in the Chesapeake

Bay, begun in the mid-1990s, have demonstrated that oyster

populations can be turned around. Until a few years ago,

however, Bay Area biologists wondered if the native Olympia

oysters still lived in the Bay in areas that could be

reached easily by researchers and volunteers who might work

on restoration. Then in 2001, Save the Bay staff and

volunteers dropped “oyster necklaces,” strings with oyster

shells tied on, into the Bay at several locations to see if

tiny oyster larvae would attach themselves to the shells and

start to grow. They did. Oysters were found at Coyote Point,

in Richardson Bay, and in Sausal Creek, next to an urban

area.

Inspired by these findings, the National

Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Fisheries,

with funding from local foundations, started two pilot

restoration projects: one in Tomales Bay started in 2003 and

the other began in Richardson Bay in 2004. Their approach

has been to place mesh bags filled with oyster shells,

weighing about 200 lbs. each, into shallow warm water where

oysters like to live. Biologist Mike McGowan, who is leading

the Richardson Bay project, explains that any oyster larvae

that may be drifting around need to settle on hard

surfaces—like the shells or reefs that have mostly

disappeared along with the oysters—in order to grow;

otherwise, they just die or get eaten.

While native oysters have not turned up on

the experimental reefs in Tomales Bay, early results for

Richardson Bay have been encouraging says McGowan. In

February, his team found dense colonies and the oysters are

large and mature enough to spawn this spring. With another

grant from NOAA, McGowan and Michele Pearson of Tiburon

Audubon will expand the restoration project in Richardson

Bay. Pearson is optimistic. She says, “Oysters won’t save

the Bay, but they’re an important piece of the puzzle.”

McGowan hopes that someday he’ll be able to pull an Olympia

oyster straight out of the Bay and slurp it down just like

the Ohlone did so long ago.

Parts of

this article are based on an article first published in

ESTUARY, a bimonthly publication dedicated to providing an

independent news source on Bay-Delta water issues, estuarine

restoration efforts and implementation of the S.F. Estuary

Project’s Comprehensive Conservation and Management Plan (CCMP).

It seeks to represent the many voices and viewpoints that

contributed to the CCMP’s development. ESTUARY is funded by

individual and organizational subscriptions and by grants

from diverse state and federal government agencies and local

interest groups. Administrative services are provided by the

S.F. Estuary Project and Friends of the S.F. Estuary, a

nonprofit corporation. Views expressed may not necessarily

reflect those of staff, advisors, or committee members.