Water …

Water … Water

From Hot Tubs To Desalination, Marin County Has

Come A Long Way, While California’s Quest For New Water Focuses On

The Sea

|

| One unit of the

600,000-gallon-per-day reservse-osmosis desalination

plant built by Ionics for the City of Morro Bay. Photo

courtesy of the city. |

By Wes Starratt, PE

More than just the land of hot tubs, Marin County

may have the Bay Area’s first desalination plant. Yes, Marin is

unique. Long ago, the growing City of San Francisco extended its

water supplies from nearby reservoirs to the more reliable and

abundant runoff of the Sierras, and the Peninsula cities tied into

the Hetch Hetchy system to ensure reliable water supplies. The East

Bay also built a water system to tap the Sierra runoff. Thus, a

substantial part of the Bay Area has a relatively reliable water

supply. Marin was different and too remote to tap into Sierra water,

so it developed its own local water system based on runoff from the

north slopes of Mt. Tamalpais.

Over the years, Marin’s water system has had its

problems, and many residents remember the last drought, almost 20

years ago, when it was mandated that residents do everything

possible to save water including taking quick showers together,

using laundry rinse water to flush toilets, and letting lawns turn

brown. Things got so bad that a pipeline was built across the

Richmond-San Rafael Bridge to tap water from the East Bay’s more

reliable system. Without that pipeline, Marin County would almost

surely have run out of water.

|

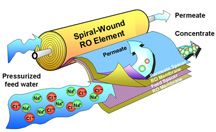

| The reverse osmosis

process: “feed water” (seawater) is pumped under heavy

pressure into outside of the tubular membrane filter;

“permeate” (potable water) flows out of the central

pipe; while the salt-containing “concentrate” exits

between the membrane layers. Drawing courtesy of Ionics. |

Mt. Tam Watershed

Later, the venerable Marin Municipal Water District (MMWD), not

wishing to repeat that near disaster, undertook an examination of

its watersheds on the north slopes of Mt.Tamalpais, looking for

additional dam sites. But there were none, although the district

found that it could squeeze a bit more water from its watershed by

raising the height of its newest dam, Kent, which it did in 1982.

The Tamalpais watershed had been extensively

developed for over one hundred years, starting in 1872, when the

Lagunitas Dam was built by a private company. It was followed by

Phoenix Dam in 1905, prior to the formation of the Marin Municipal

Water District in 1912. Watershed development didn’t end there,

however. The concrete Alpine Dam was built in 1918 and twice

enlarged. Next came the Bon Tempe Dam in 1948, and finally Kent in

1953. All of this watershed land, open to the public, created a vast

green belt on the north slopes of Mt. Tam, which continues to be

enjoyed by residents and visitors alike.

The West Marin Fiasco

Politically, water has always been an issue in Marin County, with

some residents convinced that the county’s population should be

limited by the ability to develop water supplies within county

limits. With the Mt. Tam watershed almost completely drained, and

the district facing lawsuits requiring the release of sufficient

reservoir water to maintain a fish population in Lagunitas Creek,

the district’s attention turned to West Marin.

A reservoir had been built in West Marin near

Nicasio in 1960, but its water proved to be of poor quality, and has

been used infrequently. Nevertheless, after the great drought of the

1970s, the district decided to explore the dairy farmland of West

Marin for additional reservoir sites. Finally, they thought that

they had found one, and in 1979 the district built a dam at a remote

location in West Marin, called Soulajule. Some $15 million was spent

for the dam, the water pipelines, and the pumps needed to connect it

with the rest of the system. But to this day, water from that dam is

almost never used. MMWD Board member, Jared Huffman, explained,

“Water from the Soulajule is too expensive to use because of pumping

cost and quality. The water is turbid and hard to treat; so we use

it only in critical dry years. We have used Soulajule water only

twice since we built it.” So it is obvious that somebody at the

water district didn’t do his homework, and that $15 million,

together with ongoing maintenance costs, has gone down the drain!

Desalination, A Shocking Discovery

For some time, Marin has had a keen interest in desalination (let’s

call it “desal”) as a means of solving its perennial water problems.

Thus, the district built a pilot desal plant near the Richmond-San

Rafael Bridge and operated it for four months in the Fall of 1990.

We asked Huffman what was learned from that pilot

plant. He responded, “We learned that we can desalinate Bay water.

We can treat it to state and federal standards, a level where its

quality and its taste are better than what we provide from our own

reservoirs. In our taste tests, 95 out of 100 people chose

desalinated water as tasting better.”

But cost studies done at the pilot plant came up

with the shocking figure of $3,000 per acre ft of water (a unit that

water suppliers use, in others one foot of water over an area of one

acre or 325,900 gallons). That cost compares with the cost of water

from the district’s local reservoirs of between $200 and $400 per

acre ft and wholesale water from Sonoma at $425 per acre ft before

it is piped into Marin. According to Huffman, the pilot plant’s

“very sobering” cost estimate of desalinated water “led the district

to consider Sonoma County and the Russian River as the preferred

alternative for supplemental supplies.”

|

|

|

| Marin’s Alpine

Dam, built in 1918 in the Mt. Tamalpais

watershed. Photo courtesy of Wes Starratt. |

Looking Northward from Marin

MMWD began looking northward to what was perceived to be a

never-ending source of supply, the Russian River. The North Marin

Water District was augmenting its water supplies by piping water

through a small pipeline from Petaluma to its reservoir near Novato.

The MMWD made an agreement with North Marin and Sonoma to tap into

that pipeline and began importing water from the Russian River in

the mid-1970s. But the arrangement was not without its problems. The

size of the pipeline restricted the amount of water that could be

imported, and sufficient supplies were not always available during

the dry summer months when they were needed most. Nevertheless,

water from Sonoma County continues to make up 26 percent of Marin’s

water supply. Huffman explained, “We have a long-term contract with

the Sonoma County Water Agency to provide water, but we take that

water from the excess capacity of existing facilities, and that

excess capacity is dwindling. In addition, the availability is very

constrained, especially in the peak summer period.”

The voters of Marin County were not satisfied with

that arrangement, and in 1992 they approved a bond issue that could

be used to build a major pipeline directly to the Russian River. The

promise of unending water at a reasonable price from Sonoma County

seemed too good to be true, and it was. The pipeline has yet to be

built, and has become a focal point of considerable controversy.

We talked with Randy Poole, Executive Director of the Sonoma County

Water Agency, who confirmed that Sonoma County is the nexus of all

sorts of litigation, regulatory proceedings, etc., focusing on

several species of endangered salmon, plus water diversion that has

left the Eel River almost dry during summer months, plus increasing

amounts of water demanded by the agricultural sector, “all of which

is expected to take almost 10 years to sort out,” according to

Poole. We also heard from a member of the Sonoma County Board of

Supervisors, who commented that some of his constituents are

becoming increasingly reluctant “to give away all of their water to

Marin County.” The bottom line seems to be that increasing water

supplies from the Russian River is very “iffy.”

With mounting problems in securing adequate water

supplies from that source, the district is taking another look at

desalination and considering a second pilot plant to test the most

recent advances in the technology.

Desalination is Nothing New

Desalination has been used for decades in the Middle East where

water is scarce and power is abundant. In fact, flash-distillation

of seawater is probably the main source of water in much of that

region. It requires a lot of energy, but energy is abundant in that

region, and excess natural gas is even flared just to get rid of it.

In other regions, flash distillation is used only where there is no

alternative, such as at the Guantanamo Base in Cuba.

Some years ago, a process was developed that uses

extremely fine tubular membranes to separate water from salt

molecules. For every three gallons of seawater pumped through the

membrane, approximately one gallon of potable water can be produced,

leaving two gallons of salty brine behind, which can be discharged

into the ocean. The process, called reverse-osmosis or RO (the

reverse of the natural process found the plant world), requires

considerable pressure, meaning electrical power, to force the water

through the membrane. Thus, electrical energy is the number one cost

of operating such plants; however, RO requires much less energy than

flash distillation, and improvements continue to be made in membrane

technology that reduce the pressure, hence energy, required to force

the water through the membranes. RO plants comprise three distinct

elements: a pretreatment step to remove sludge and other matter that

would foul the membranes, followed by RO filtration, and a final

step to adjust the chemical balance of the water.

In California, RO desalination has been used for a

number of years to provide boiler feed water for coastal power

plants. In the early 1990s, California’s largest desal plant was the

600,000 gallon per day (gpd) RO plant built and operated by Ionics

at PG&E’s Diablo Canyon nuclear power plant. Later, Catalina Island

put in operation the West Coast’s first plant to augment local

supplies with desalinated water. That 200,000 gpd RO desal plant

continues in operation by Southern California Edison at the island’s

power generating station.

|

| Mt. Tamaplais and

the Bon Tempe Dam, built in 1948, one of five dams

operated by the Marin Municipal Water District in the

watershed. Photo courtesy of Wes Starratt. |

During California’s drought of the 1990s, a number

of coastal communities faced severe water shortages. Santa Barbara

was one of them. The city built and operated America’s largest RO

plant, producing 10 to 12 million gallons of water per day (Mgd).

Further up the coast, Morro Bay tapped the Ionics firm to design,

build, and operate an RO plant similar to Diablo Canyon plant.

Finally, the rains came, and Santa Barbara was able to tie into the

California Water Project, which provided water at half the price of

desalinated water. So, Santa Barbara put its RO plant into a

“long-term storage mode,” while Morro Bay, without the benefit of

imported water, retained its facility for operation “as needed.”

Desalination Continues to be of Growing Interest Throughout

California

As California’s population continues to grow, as its agricultural

industry continues to feed much of the nation, and as drought

conditions continue in the Colorado River basin, and while politics

dictate against developing new dams and expanding existing ones, the

state’s demand for water outpaces supplies by an estimated 2 million

acre-feet per year. Conservation and recycling are being pushed,

even to the extent of discouraging green lawns in desert areas like

Las Vegas. For all of these reasons, it is not surprising that there

is a growing interest in seawater, as well as groundwater,

desalination, especially in those areas with the most population and

the least water, namely the coastal areas of southern California.

In September 2002, the State Assembly called upon

the California State Dept. of Water Resources to establish a

“Desalination Task Force” that would make recommendations on

opportunities for seawater desalination. The task force concluded

that desalination is “a proven, effective mechanism for providing a

new source of water.” The report noted that the cost of desalination

has dramatically reduced from about $2,000 per acre-foot to less

than $1,000 as the membranes used for the RO process have been

improved in efficiency and longevity.

When the report was issued late last year, there

were “sixteen relatively small ocean desalination facilities in

operation” in California, several of which provide water for coastal

power plants. Today, “Nineteen new ocean and estuarine desalination

facilities are in various stages of planning” in plant sizes ranging

up to 50 million gallons per day (Mgd) for a state total of 213 Mgd.

The Desalination Report stressed the importance of co-locating

“desal” plants with existing coastal power plants, since such sites

provide compatible industrial land use at a coastal site, offer the

use of existing infrastructure for both feed water intake and brine

discharge, and have the all-important potential of purchasing power

at wholesale rates. Unfortunately, Marin County offers no coastal

pilot-plant site.

Most of the Action is in Southern California

Southern California’s leading water wholesaler, the Metropolitan

Water District (MWD), made up of 26 member water-supply agencies,

stretching from Ventura County to the Mexican border, has embarked

on a comprehensive program to stretch water supplies through a

variety of programs including seawater desalination. MWD is offering

to pay its member agencies an incentive of $250 per acre ft for up

to 150,000 acre feet of desalinated water for a period of 25 years.

That incentive should bring the cost of desalinated seawater down to

about $750 00 per acre ft, which begins to approach the $500 to

$600/acre foot for water imported from northern California by the

California Water Project.

Thus far, five water agencies have signed on to

MWD’s program…San Diego, Orange County, Long Beach, West Basin, and

Los Angeles…for a combined capacity of 126,000 acre feet of

desalinated water per year. The most ambitious project is proposed

by the San Diego County Water Authority, which is holding

discussions with Poseidon Resources Corp. to expand the firm’s pilot

plant at Carlsbad to an operating plant of 50 Mgd capacity, which

would make it the largest desal plant in the United States.

And in Northern California

Numerous California coastal communities are also facing water

problems. In the Monterey Bay area, the City of Santa Cruz is busy

writing an EIR in collaboration with the Soquel Creek Water District

for a 2.5 to 4 Mgd desal plant. The plant not only can be expanded

on an incremental basis, but can be operated when needed during the

dry summers, thus offering something more flexible than a

hydroelectric project. On the other side of Monterey Bay, Sand City

is writing an EIR for a small desal plant using beach wells. Other

local desal plants include a small unit at the Monterey Bay Aquarium

and a larger plant to provide boiler feed water for the Moss Landing

power plant.

A Red Flag at Tampa Bay

But RO seawater desalination is not without problems, among them is

the fouling of membranes due to the inadequate pretreatment of

intake water. Such is the case for what is currently the country’s

largest desal plant, a 25 Mgd plant using cooling water from a power

plant on Florida’s Tampa Bay. That desal plant was supposed to start

up last year, but has only operated intermittently, driving the

plant designer into bankruptcy and producing law suits that will

keep attorneys busy for some time. Numerous solutions have been

proposed, and it appears that the problem lies with the intake water

and the pretreatment system. In any case, desalination enthusiasts

are closely watching developments at Tampa Bay.

Back to Marin County

The Board of the Marin Municipal Water District, faced with a

potentially unreliable source of future supplies from Sonoma County,

is determined to learn more about whether or not desalination is the

right answer to Marin’s future water needs, especially during

extended droughts and long dry summers. The ultimate goal is a 10

Mgd plant that could be operated on an as-needed basis. But, first

comes more pilot-plant testing, especially in light of the problems

encountered at Tampa Bay. After all, Marin’s proposed desal plant

would be the only other major desal plant not to utilize seawater,

and San Francisco Bay water can be pretty brown with silt during wet

winter months, although it does have the advantage of a lower salt

content than ocean water. Thus, in October, the MMWD Board is

scheduled to vote on whether to build a second pilot plant.

We asked Huffman, “Why do you need a second pilot

plant?” He responded that, “We know that the economics have gotten a

lot better from enhancements in membrane technology, but what we are

really curious about is new pretreatment technology. That includes

micro-filtration, which requires much smaller space. That is

important for our proposed desal plant site, which will be located

on the old San Rafael landfill. Also, micro-filters extend the life

of the RO membranes and can be less energy intensive. We want to

understand that technology and try different types of micro-filters

so that we don’t make the mistakes that they made at Tampa Bay where

they cut corners and didn’t properly brake-in and design the

micro-filtration system.

“We will be looking for financial partners from

the membrane industry and other agencies that are interested in this

kind of pilot testing. So, the price tag for the pilot plant should

be substantially less than $1 million. With approval at the October

Board meeting, the pilot plant can be in operation before the end of

the year so that we can test it during the rainy season and under

varying conditions of salinity and sediments.

“We also hope to learn more about the removal of

other toxics and turbidity from Bay water and test for everything

that might be in the Bay water. And, by the way, all of those things

are also in the Russian River water.

“From the pilot plant, we will be able to develop

capital and operating costs for the full-scale plant. We want to

move as fast as possible with the design and construction of that

plant, and the EIR should be certified by the spring of 2005.”

Marin’s full-scale plant will be based on a permit for a 15 Mgd

plant, but it will likely be built in modules.” Huffman guesses

that, “10 Mgd is the most effective size for the needs we face.”

We also asked Huffman how much he expects the

water from that desal plant to cost. “Realistically between $1,000

and $1,500 per acre ft. It will be at least double the cost of water

out of our reservoirs, but it will be similar to what we think the

Russian River water will cost over time. We know that desal water

will be high quality, and it will be there when we need it. Also, we

can use it only when we need it, as contrasted with Sonoma water,

which we must take whether or not we need it.”

Furthermore, “Legislation is pending in Sacramento

that will permit desal operators to negotiate directly for preferred

energy prices. And legislation is pending in the U.S. Congress that

would provide a $200 per acre foot power subsidy to desal plants.”

California’s Bottom Line

The bottom line is that local run-off water is undoubtedly the

cheapest water for Marin and other California coastal communities,

but it is available seasonally and only in limited amounts,

especially during drought years. To ensure reliable water supplies,

coastal communities from Marin to San Diego are looking at seawater

desalination to provide the balance of their water supplies. Thus,

Marin residents, along with those of other coastal communities, can

expect to pay more for water, unless either the state or the federal

government can be persuaded to subsidize power costs. There appears

to be no other alternative as California’s growing quest for water

focuses on the sea.