For more than twenty years, the wine industry has convinced people that fine wine has a cork. That mindset must change. Alternate forms of bottle closures must be explored and ultimately accepted. There is a problem with our old friend The Cork. Wine production is being accelerated all over the world in every region that will bear vines. This is pushing hard on cork producers to keep up with demand and like any other agricultural product,

Murphy-Goode has good answer to the growing cork shortage.

Published: September, 2003

For more than twenty years, the wine industry has convinced people that fine wine has a cork. That mindset must change. Alternate forms of bottle closures must be explored and ultimately accepted. There is a problem with our old friend The Cork. Wine production is being accelerated all over the world in every region that will bear vines. This is pushing hard on cork producers to keep up with demand and like any other agricultural product, quality suffers with high volume output. In years past, cork was harvested from trees eight to ten years old. Now corks are made from four year old trees grown in forests which are too large due to increasing demand.

So what’s wrong with the modern cork? Some of them contain a "dead spot"--a little pocket of bad cork, which reacts with the wine as it rests in the bottle creating a compound known as 246 Trichloricanisol, which is the cause of cork tainted or what is simply called "corked wine." This compound flattens out or dulls what is referred to as "the mid-palate fruit." There may be fruit at the beginning and a decent finish at the end, but the wine has no character--the middle is "hollow." This is capped off with a musty smell not unlike old wet cardboard.

Fifteen years ago, 1-2 out of 100 bottles had this syndrome. Now it is 6 - 8 out of 100. These bottles are generally returned to the vintner, but the real problem is unreported cases where someone buys a wine they once enjoyed in the past-- it’s a little cork tainted--it has no character, they don’t know it’s corked, they just don’t like it and won’t buy it again. Lost customers rarely return.

Some vintners tried plastic corks, which are hard to pull, plus one can break the bottle during the removal process. Even though the cork is synthetic, it implies the wine could be laid down for a year or two but when revisited, it tastes like plastic--another problem to fix.

One way to fix it is with a twist top cap, according to Mark Pape, marketing coordinator for Murphy Goode Winery in Geyserville. Their Chardonnay, aptly called "Tin Roof," is on the cutting edge of twist- top technology. Unlike typical wine screw caps, they use a Canadian process called a Stelvin Closure, which uses specially molded caps made of a thicker gauge metal, which are pressed onto the bottles. It’s not actually a twist top until the wine is opened. The message is: Take this wine home and drink it tonight knowing it would likely be less tannic, less oaky, more fruit driven.

There is an atmosphere in an aging bottle of corked wine. It involves dissolved oxygen in regards to the cork’s reaction with the wine itself and the airspace in the bottle. This reaction is responsible for the more sophisticated aspects of aged wine such as "bottle bouquet." The twist top is hermetically sealed, so for immediate consumption, it makes sure the wine is in the same condition as when it was bottled. How it will affect the ageability of wine is the curiosity. Will it allow dissolved oxygen at the rate to age a premium red wine at a natural pace, or will there be side effects like the plastic corks?

Murphy Goode is bottling each varietal both corked and twist topped under identical conditions, which will be revisited every six months to watch how they develop. There will also be chemical laboratory analysis to see how they differ, particularly with regard to dissolved oxygen. Slowly, over time, age-worthy wines will be available with twist-top closures once they prove themselves. This is tricky because the wine industry has instilled the importance of a cork. For now, high quality wines will have one.

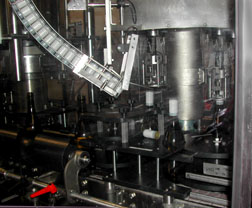

To dispel the notion that the Stelvin Closure is just a cheap package, the specially molded caps and bottles are actually more expensive than regular bottling. The machine, that accomplishes this is a marvel. Completely enclosed in glass, the bottles are unboxed by hand and sent into the first stage--a large wheel called the orbiter. When each bottle is upside down, it is blown out with air to remove any dust and is then "sparged"--filled with dry nitrogen, which is heavier than air. The bottles move to the second stage where they are filled with wine and then onto stage three where the cap is dropped onto the neck and pressed into place. After that, out of the machine to be boxed by hand. Be assured at this point, the wine will never be cork tainted!

To look elegant when opening, grasp the Stelvin Closure firmly with a dampened towel and turn the bottle. Never again will the cork be accidentally pushed into the wine. There is, however, one drawback with the twist top. All our lives, our mothers told us to "put the cap back on." So when pouring a second glass of wine, it won’t come out of the bottle. But you’ll know what to do . . .