Treasure Island is about to get a serious, top-to-bottom green makeover.

Image courtesy of SOM

By Bill Picture

Published: March, 2008

With the overhaul of the man-made island, which has sat largely idle since its former occupant, the Treasure Island Naval Base, vacated in 1997, it will serve as a showcase for green design, green urban planning and sustainable living.

The master plan for the island, which is still a work in progress, calls for more than just the usual green flourishes. In fact, the idea is to create a self-sustaining city of the future. The plan is a collaboration between the City of San Francisco, sustainability advisors Arup and Treasure Island Community Development (TICD), and a team of developers led by Lennar Corporation. We typically try to cover all aspects of sustainable urban development, says Jean Rogers, a sustainability consultant with Arup. Some projects are more successful than others at integrating sustainability strategies. It usually comes down to financing.

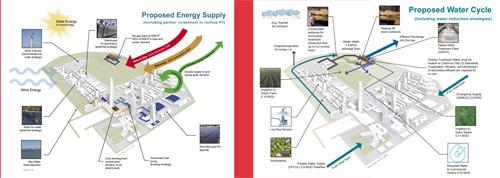

Among the project’s impressively long list of green elements, which will be paid for with a combination of private dollars and bond money, are a working organic farm fertilized with all of the food scraps and grass clippings generated on the island, carbon-eating wooded areas, and a wind farm, whose mills, together with smaller building-mounted turbines and acres of rooftop solar panels, will produce enough clean juice to support the island’s grid and supplement the state’s existing supply of renewable energy. Engineers are also looking into installing underwater turbines in the surrounding bay to harness the energy of the tides in the Golden Gate Channel.

Michael Tymoff of the Treasure Island Development Authority (TIDA), the governing body created by the City of San Francisco to oversee the redevelopment of the island, says that sustainability was a key element of the project from the very beginning. In fact, he says a high green bar was set for the project even before the word green became a commonly used symbol of environmentalism. That standard was established in the mid-1990s, shortly after the Navy announced its plan to close Treasure Island Naval Base and return the island to civilian use, when the City of San Francisco, with the help of a citizens advisory committee, drafted an initial set of general guidelines for future redevelopment.

The ideas of environmental protection and stewardship were strongly worked into those original goals, Tymoff explains. I don’t think the words ‘green’ or ‘sustainable’ were actually used. But the intent was definitely there.

Those general guidelines would later be used by TIDA to draft a Request for Proposal, in which strict green requirements were set forth as part of the permitting process. From the developers that bid on the project, the Lennar team was eventually selected, based on the comprehensiveness of its proposed green to-do list. That list is now being carefully looked at and refined, based on the advice of various independent third parties. While some of the ideas of a green city might seem like science fiction, the technology that will be utilized is very much present day. Still, TICD and TIDA have hired architects and consultants to review the technology’s application on a block-by-block basis to figure out what will actually work.

A final plan is expected to be presented to the City of San Francisco for approval by the end of 2009. And, if all goes well, the project will get underway in early 2010.

TICD’s first order of business will be preparing the island for construction. The buildings on the island will be leveled in staggered phases, surrounding roads will be cleared and soil readied. And, because it was built on landfill, the entire island must be stabilized in order to meet today’s seismic safety standards.

Engineering practices in 1939 [when the island was built,] weren’t quite up to today’s standards, Tymoff explains. So we’re talking about $800 million worth of work before construction can even begin. But, when predevelopment is completed, TICD will get to start from the scratch it created. And that will help ensure that the subsequent new infrastructure is the smartest, most cutting edge and lowest impact.

For instance, the existing sewage treatment plant on the island will be replaced with a new, state-of-the-art facility. Instead of dumping all of the treated water into the bay, at least a quarter of it will be recycled for use in flush toilets, and used to irrigate the on-island farm. The new grid of streets planned for the island will be oriented 35 degrees west of due south to maximize solar exposure and offer protection from the constant breeze that chills the island. That will mean less energy needed to heat, cool and light homes and businesses.

The first of 6000 residential units, 90% of which will be located within a ten-minute walk of the island’s new downtown area and ferry terminal, thus minimizing car use on the island, will be ready for occupancy by 2015. Those units will be housed in a combination of high-density residential towers and low-rise buildings, all built to standards comparable with the Green Building Council’s Leadership in Energy & Environmental Design (LEED) Green Building Rating System.

The standards represent an equivalent level of performance, Rogers explains. [But] this will save the developer tens of millions of dollars on administration [costs] associated with LEED certification.

The sustainability plan for Treasure Island is the first of its kind for two reasons: first, because of its scope, and second, because it is a legally binding agreement between the developers and the City of San Francisco. In other words, TICD is legally obligated to execute every one of the items on its final to-do list.

It not just a visionary document full of sustainability platitudes, but represents commitments that the developer needs to achieve, explains Rogers. That was a major achievement.

Yet another impressive aspect of the plan for the island is the flexibility that it allows for the inclusion of emerging technology. The technology that TICD has proposed to use is all state-of-the-art right now. But the project is expected to take between ten and fifteen years to complete. And it is quite likely that, within that time, something greener could come along. If it does, all parties involved want to make sure that there is some wiggle room in the master plan for new technology, once it is proven, to be applied on Treasure Island.

Probably what we will see are significant advances in wind and solar capabilities that will result in far greater efficiencies and capacity, for the same price, Rogers explains.

The goal, according to Tymoff, has always been for Treasure Island to exemplify the best practices of environmentalism. And, in order to do that, he says that the redevelopment team must keep its eye on the future. There are things that are out of reach today that may be feasible in five years, he adds. We want to remain open to those possibilities so that we can continue to refine and improve our plan for the island as the green tech revolution continues to evolve.

Images courtesy of Arup