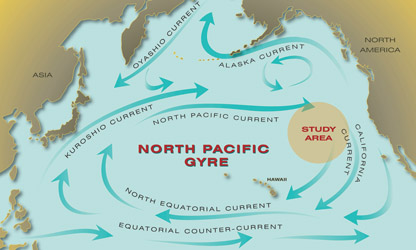

A few hundred nautical miles off the coast of California, ocean currents collide to create a swirling vortex known as the Pacific Gyre. At the center of that vortex lies a fast-growing pool of garbage—most of which is terrestrial in origin—that environmentalists have dubbed "The Great Pacific Garbage Patch."

The North Pacific Gyre is a giant vortex that lies between Asia and North America cause by prevailing currents. Illustration by Jean Kent Unatin

By Bill Picture

Published: April, 2008

You see, the same salty breezes that keep Bay Area air so fresh also have a tendency to pick up litter from city streets and deposit it into the San Francisco Bay. Changing tides in the Bay and its grid of currents catch most of the garbage, creating floating tangles that often hug spots along the Bay’s shoreline, threatening the native wildlife with whom we share the region.

But, with the help of a strong, Pacific-bound current, some of the trash will find its way to open water, and make the slow journey to the center of the Pacific Gyre. Some of the garbage will biodegrade along the way, but non-biodegradable refuse, such as plastics, will survive the journey and, eventually, be deposited into the garbage patch. This isn’t a small problem; the patch is now roughly twice the size of the state of Texas!

Calling it a garbage patch isn’t really accurate, explains Marcus Eriksen, Director of Education and Research at Long-Beach-based Algalita Marine Research Foundation (AMRF). The best way I can think of to describe it is a vegetable soup. The noodles would be the 2.5 tons of fishing nets. The vegetables would be the plastic bottles, shampoo bottle caps, fishing floats and the odd shoe or flip-flop. And the majority of it is the broth, a thin soup of partially broken-down plastics.

Plastic isn’t biodegradable. Instead, it photodegrades, meaning sunlight breaks the plastic down into smaller and smaller, but no less toxic, parts, until it reaches molecular level. It’s at this level that plastic is most dangerous, as it can very easily be ingested by sealife.

Though founded in 1994, AMRF’s mission wasn’t cemented until 1997, when its founder, Charles Moore, a researcher and avid yachtsman, sailed right through the center of the garbage patch on his way back from a yacht race in Hawaii. Since then, the foundation’s efforts have been directed toward stopping the growth of the garbage patch, by raising awareness of the problems caused by water-carried pollution.

AMRF’s scientists have been back to the garbage patch several times since 1997 to conduct research. They’re particularly interested in determining the patch’s growth rate. And, while the results of their latest trip are still being assessed, Eriksen says the patch is growing exponentially, which he believes is largely due to the increased use of plastic packaging, particularly for items marketed as disposable.

I don’t want you to think that [AMRF] is anti-plastic, because we’re not, he explains. We just don’t think that our culture of one-time usage is a smart, sustainable practice. We need to change that kind of culture and get away from this ‘use it and toss it’ mentality.

While we’d all like to believe that every plastic bottle and container gets recycled, this is far from the truth. In fact, according to Conservation International, less than 25% of plastic bottles are recycled. The rest are landfill-bound, or end up in gutters or storm drains. In San Francisco, storm drains flow to wastewater treatment facilities, where garbage is removed. But in every other city in the Bay Area, the drains go straight into the Bay, explains Jessica Castelli of Save the Bay, an Oakland-based non-profit dedicated to protecting and restoring the San Francisco Bay.

Castelli estimates that 90 percent of the trash that ends up in Bay Area waterways is non-biodegradable. And a very good portion of that, she says, is plastic. Though she commends Bay Area consumers and businesses on stepping up their recycling efforts, she agrees with Eriksen that recycling isn’t a magic bullet.

The San Francisco Bay Regional Water Quality Control Board did a study recently, and they found three pieces of trash in every foot of stream and creek leading into the Bay, she explains. And coastal cleanups happen regularly, and we still find tons of trash. What we need to do is create less trash, and be more careful about our trash.

Castelli also believes that stronger policies and regulations need to be in place at the city and county level. It’s time that we make [local governments] accountable because, until now, restrictions on trash haven’t been enforced as strongly as other runoff pollutants.

Save the Bay recently advocated for the SF Bay Regional Water Quality Control Board [WQCB] to require that Bay Area counties greatly reduce trash discharge into the Bay via storm drain runoff, or be subject to penalties. Despite opposition by local governments, who argued that meeting the board’s new requirements would be costly and burdensome, the WQCB decided last month to proceed with the plan. The new requirements will go into effect in a few months.

That’s the best thing we can do, stop more trash from getting into the water, says Marcus Eriksen of the Algalita Marine Research Foundation. And that’s where small communities can take the lead.

San Francisco has done more than any other Bay Area county to minimize the amount of plastic that ends up in landfills and in the Bay. It was the first to ban the use of Styrofoam takeout containers by restaurants. A handful of other Bay Area cities have since followed suit.

The City is also in the process of phasing out the use of bottled water in city offices and was the first to ban the use of plastic shopping bags by large supermarkets. Film plastic is insidious stuff, says Alex Dmitriew, Assistant Coordinator of the San Francisco Department of the Environment’s Commercial Zero Waste Program. It blows around and end ups in the Bay. And it causes havoc in the marine environment. Later this year, the City of San Francisco will ask restaurants and other hospitality-related businesses to voluntarily stop selling bottled water. And the City is considering a ban on the sale of single-serving bottles of water in San Francisco.

Dmitriew believes that such restrictions on the commercial use of plastic are a good start. But he says that consumers must also accept some responsibility. We need to think more when we make purchases and start making smarter choices, he says. Eriksen adds, Disposable is just a giant waste of resources. Take your own bags when you go shopping, use a coffee mug instead of a disposable cup, stop using straws.

Unfortunately, researchers have yet to come up with a solution to the Great Pacific Garbage Patch. There is no cheap, easy or effective way to remove the garbage. And researchers fear that any attempt to do so might kill off the zooplankton that call this stretch of ocean home.

Still, Eriksen insists the situation isn’t hopeless. We need to focus on what we can do, he says. And that’s stop making the problem worse. You should see the look on people’s faces when they see one of the samples we took from the [garbage patch]. They’re appalled, and they go, ‘What can I do?’ I think people inherently want to the do right thing. They just need to be guided.

For more information visit the following websites:

Algalita Marine Research Foundation - www.algalita.org

Save the Bay - www.savesfbay.org

SF Department of the Environment - www.sfenvironment.org

All images Courtesy of Algalita Marine Research Foundation

Above and below: Items collected from open waters in the Pacific Gyre.