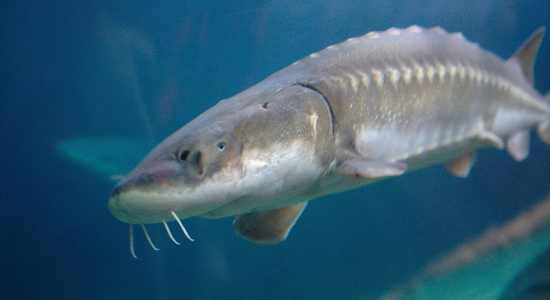

These are common questions and reactions heard in Aquarium of the Bay’s iconic tunnel exhibits when visitors take their first close-up look at white sturgeon (Acipenser transmontanus).

Photo by Matthias Lust, Aquarium of the Bay

By Kati Schmidt

Published: August, 2010

“Is that a shark? It looks like a swimming dinosaur. What the heck is that?”

These are common questions and reactions heard in Aquarium of the Bay’s iconic tunnel exhibits when visitors take their first close-up look at white sturgeon (Acipenser transmontanus). At record-setting sizes of more than 1,300 pounds and 13 feet long, white sturgeon hold strong to their title of the largest freshwater fish in North America.

But white sturgeon are more than just freshwater fish. Similar to salmon, white sturgeon are anadromous, meaning they go both ways—thriving in freshwater and salt-water conditions, that is. While the goliath-sized white sturgeon was reported before the 1900s, according to the California Department of Fish and Game, the largest sturgeon caught in San Francisco Bay in the past 40 years was a 468-pound fish landed in 1983 by a sport angler fishing in the Carquinez Strait.

“White sturgeon are the granddaddy of fish in our rivers,” said Crystal Sanders, fisheries biologist and conservation coordinator at Aquarium of the Bay.

When first born, the sturgeon’s skeleton consists entirely of cartilage. As the fish matures, a process that takes between eight and 20 years, the cartilage ossifies, or turns into bone. However, instead of having scales, white sturgeon have five rows of scutes—a sort of natural body armor of hard plates—covering their bodies.

White sturgeon have small, beady eyes, making natural vision limited. The animal mostly relies on its barbels, which are often described as “whiskers,” on the side of its mouth, which help them sense and feel out food.

“Using their proboscis mouth, which is akin to an elephant’s trunk, the sturgeon’s mouth shoots out, to help them suck food out of the sand,” said John Krupa, aquarist II at Aquarium of the Bay. According to Krupa, who helps care for the aquarium’s nine sturgeon, the species is not too particular in its diet. Because it lacks teeth, however, it prefers softer foods, such as insects and worms during its younger years, before moving on to a more discerning palate of squid, fish and the occasional crustacean or mollusk once it matures.

The dinosaur-focused visitor reaction to white sturgeon really isn’t so far off. From fossils, many scientists believe sturgeon evolved around 260 million years ago, meaning they were around before even the oldest dinosaurs roamed the earth. According to the California Department of Fish and Game, sturgeon skull plates and scutes have been found in Native American middens, or dumping grounds, in San Francisco Bay, the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta and Elkhorn Slough areas, supporting belief that the animal was an important source of nutrition.

The Department of Fish and Game reports that locally, commercial fishing for the animal in San Francisco Bay and the Delta rose to an all-time high in 1887, when 1.65 million pounds were harvested. This number declined over the years until 1917, when local commercial fishing was brought to a halt. Sport fishing, while regulated with size and weight minimums and maximums, was first legalized in 1954.

While white sturgeon have a slow growth rate, they are very long-lived and have the opportunity to spawn multiple times, unlike the also anadromous Pacific salmon, which dies after spawning. Sturgeon spawn in rivers, and can release anywhere from 100,000 to more than one million eggs at a time.

While the animal’s protective armor does make it “the King of the rivers,” according to Krupa, their most common threat are people, both through commercial fishing and through human-made dams to rivers, which decrease spawning habitat.

Nine out of the 10 major tributaries leading into San Francisco Bay are currently blocked by large dams in the foothills for water storage, diversion and flood control. According to Tina Swanson, executive director and chief scientist with the Bay Institute, these reductions in freshwater flow harm the overall health of the estuary and watershed ecosystems and have degraded its ability to support its valuable fisheries and wonderful fish like white sturgeon.

Kati Schmidt is the Public Relations Manager for Aquarium of the Bay and The Bay Institute, nonprofit organizations dedicated to protecting, restoring and inspiring conservation of San Francisco Bay and its watershed. A Bay Area native and aspiring Great American novelist, Kati enjoys the professional and personal muses found from strolling and cycling along, and occasionally even swimming in San Francisco Bay and beyond.