Some of the highest tides of the year take place February 7-9, giving the Bay Area a preview of what’s coming as global climate change raises sea levels.

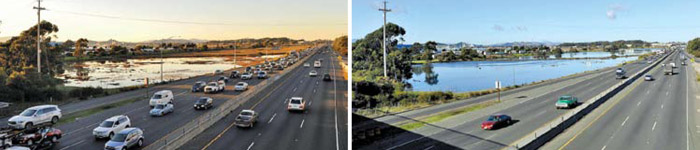

Above, wetlands along the Richmond shoreline at low tide and during an exceptionally high tide. Wetlands can help prevent flooding that will hit the Bay Area as global climate change causes sea levels to rise. But rising sea levels threaten to drown wetlands and destroy their protective value. Wetland habitat can migrate uphill a little as sea level encroaches, but not if nearby lands are paved over, as these are with Interstate 80. Photo credit: tmikkphoto (Flickr Creative Commons)

By Deb Self

Published: February, 2013

Some of the highest tides of the year take place February 7-9, giving the Bay Area a preview of what’s coming as global climate change raises sea levels.

These exceptionally high tides are called king tides. They occur every year when the gravitational pulls of the sun and moon reinforce one another. While not caused by climate change, king tides allow us to visualize now how more frequent flooding caused by rising sea levels will impact San Francisco Bay’s shore and shoreline communities.

During December’s and January’s king tides, Bay waters washed up on the sidewalk along San Francisco’s Embarcadero. Streets in Sausalito and other Marin coastal communities flooded, along with shoreline roadways and parking lots in the South Bay. As sea levels rise over the coming decades, this type of flooding will happen along more of the Bay’s shore with increasing frequency.

Climate change is also bringing more severe storms worldwide, like last fall’s Hurricane Sandy on the East Coast. While the Bay Area is not under threat from hurricanes, an intense storm here, combined with higher sea levels, could cause widespread flooding and damage. It will be even worse if a big storm hits during a king tide.

Up until 150 years ago, the region’s shorelines had some natural protection from high water storm surges, thanks to abundant wetlands. Wetlands are communities of plants and animals adapted to being underwater or partly underwater at high tide and exposed or partly exposed at low tide. They soak up water like a sponge and stabilize shorelines.

Although about 90 percent of San Francisco Bay’s wetlands have been eliminated, the remaining wetlands are essential to the Bay’s ecology. Over recent decades much public money has gone into restoring Bay wetlands, but rising sea levels now threaten to completely submerge many of these ecologically valuable areas, destroying their protective value.

If there is undeveloped land uphill from the wetlands, then, as Bay levels rise, resilient wetland plant and animal communities may be able to migrate to slightly higher ground and preserve natural protection for shorelines. But much of the Bay’s shoreline has been paved over with highways, homes, and industrial and commercial facilities, leaving no place for wetlands to move upland. As sea levels rise, wetlands next to developed shoreline all around the Bay are under threat.

Some of this future damage can still be averted with smart planning. To preserve nature’s flood control protection, our region should prevent any more development or paving on land next to the Bay’s remaining wetlands, as well as wetlands that are being restored. It also makes sense not to put thousands of new homes or massive commercial development on land that will be flooded soon. You can help lessen the impact of climate change on the Bay Area by letting your local leaders know that you support development policies that protect the Bay, local communities and the shoreline.

Deb Self is Executive Director of San Francisco Baykeeper, www.baykeeper.org. Baykeeper uses on-the-water patrols of San Francisco Bay, science, advocacy and the courts to stop Bay pollution. To report pollution, call Baykeeper’s hotline at 1-800-KEEP-BAY, e-mail hotline@baykeeper.org, or click "Report Pollution" at www.baykeeper.org.