With a recent memo, the San Francisco Port Commission has officially prioritized reinforcing the seawall that protects the waterfront property stretching from Fisherman's Wharf to Mission Creek.

Photo by Joel Williams

By Bill Picture

Published: May, 2016

With a recent memo, the San Francisco Port Commission has officially prioritized reinforcing the seawall that protects the waterfront property stretching from Fisherman’s Wharf to Mission Creek.

San Francisco was recently extended a helping hand with this effort by Citi Foundation and Living Cities. The partnering organizations’ two-year-old City Accelerator program not only contributes seed money to kick-start vital infrastructure projects like San Francisco’s seawall fortification, but also helps city governments to identify sources of additional money to close funding gaps and affords participants the opportunity to pow-wow with agencies dealing with similar challenges in other parts of the country and around the world.

Seattle is in the process of replacing the seawall that protects its downtown area and tourist epicenter, to the tune of about $500 million for a one-mile stretch. San Francisco is sure to pick the brains of city officials there, as well as those involved in recent seawall projects in Miami and London.

“But we’re talking about fortifying existing seawall rather than replacing it,” said Interim Port Director Elaine Forbes. “In fact, we’re actually talking about stabilizing the soil that the seawall was built on, and the land behind it. The seawall itself is actually in good shape, we think.”

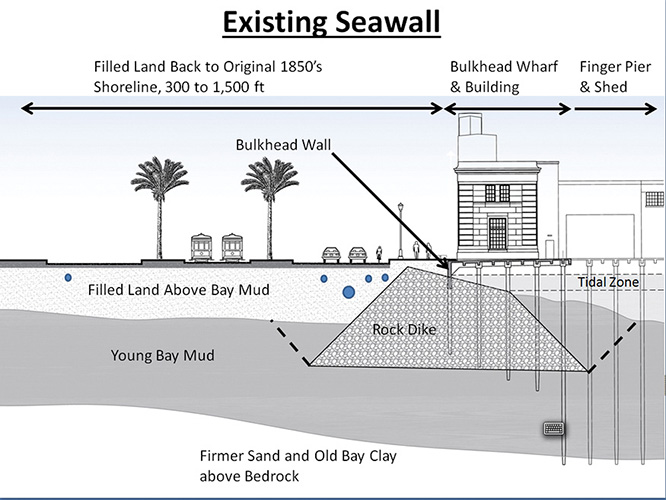

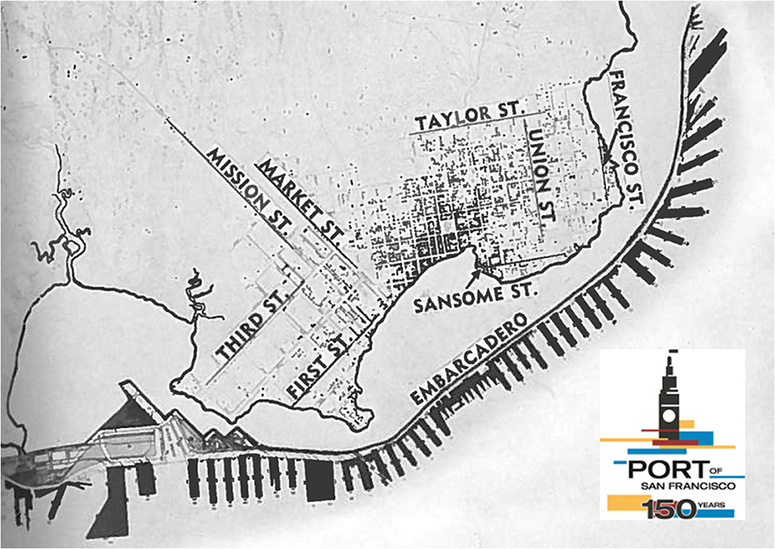

San Francisco’s seawall was built more than a century ago to hold back water after 300-plus acres of the Bay were filled in to expand the City’s geographic boundaries and create what is now considered prime waterfront real estate. The wall itself is sturdy even by today’s standards; and most everyone expects it to weather a major earthquake well. The same cannot be said, however, for the soggy clay that the wall was built on top of and the reclaimed land behind the wall.

“The composite soil and filled land both behave very badly in earthquakes,” Forbes said. The commission’s memo predicts that a good shake may cause the clay to settle or spread, the filled-in area to liquefy (a well-known phenomenon called “liquefaction”) and push against the wall. This could cause the seawall itself to be pushed forward into the Bay as much as a foot in some places—thereby threatening the wall’s structural integrity.

Given that billions have been spent developing the reclaimed land behind the seawall and installing (and maintaining) the infrastructure needed to sustain that development, a wobbly seawall would be very, very bad news. Along with the blow dealt to occupants of the many commercial and residential properties along the waterfront, some of San Francisco’s most-visited tourist attractions would be threatened.

“The money that Fisherman’s Wharf and Pier 39 generate is huge,” Forbes said. One out of every four visitors to San Francisco spends some amount of time and money at the waterfront.

“The seawall not only protects expensive real estate; it also benefits a lot of different agencies,” Forbes continued. “MUNI has invested money along the waterfront, the Public Utilities Commission, just to name a few.”

The fact that the failure of the seawall would impact so many different public and private entities presents numerous potential sources of funding. “We need to figure out how to leverage that,” Forbes said. Naturally, San Francisco will call upon state and federal agencies to chip in. “But the final mix could include private money as well,” Forbes said. “To come up with the money that we need, we’ll need to identify multiple sources of funding, and different types of sources. We really can’t afford to leave any stone unturned.”

Prioritizing danger

With a major earthquake and sea level rise both threatening to devastate the waterfront, San Francisco has been forced to prioritize these threats and prepare accordingly. And because scientists say California is long overdue for a 1906-like earthquake, preparations for that seeming inevitability now sit on the front burner.

“In terms of which is the more pressing danger time-wise, it’s definitely earthquakes,” Forbes said. “We have some time to figure out how to address sea level rise. It’s the more patient of the two problems.”

Plus, sea level rise poses an ongoing threat that many generations to come are doomed to inherit.

“With seismic readiness, we fix the wall and it’s done,” she said. “Because we don’t have unlimited resources, we have to focus on problems that we believe we can fix. Sea level rise is going to require a plan that can change and adapt as the threat itself does.”

Forbes pointed out that should a major earthquake compromise the seawall before it can be stabilized, San Francisco risks losing a major lifeline. “I think we forget the important role that the port would play during a major disaster,” she said. “If bridges or roads were out, the Bay would become an important means of transportation and the port would play a key part in the moving and staging of supplies. It’s easy to forget that, because San Francisco is no longer an active container port.”

Once San Francisco has determined which sections of the seawall need the most attention, Forbes estimates it will take two years to complete the planning and design phase, and then do the necessary public outreach. Waterfront access for the public will have to be maintained, and the work will have to be staged so that access is impeded as little as possible.

“We’d also want a proof of concept to make sure that what we’re proposing is actually going to work,” Forbes said. “And what works for one section may not work for some of the others. We won’t know until we test it out.”

Forbes predicts that if all goes well, work will begin in earnest within five years. “And we’d like to see major improvements completed within an eight- to ten-year timeframe. That may seem like a long time to some people, but that represents a major streamline,” she said. “This is a really big project, and that timeline’s really full-throttle.”

The Great Seawall was constructed 1878 - 1915. More than three miles long, it created over 700 acres of new land that was previously under water.