Ferries and trains interconnected all over the Bay Area until roads metastasized and killed the system off. A pale imitation of national rail service staggers along in the form of Amtrak, though auto and gas servitors in Congress do their best to run it to ground. Eventually, ferries and trains will return (albeit at staggering cost). Our very own cantankerous Guy Span gives his take on how Amtrak has fared.

Published: July, 2003

Railroad passenger trains were in trouble years before they were nationalized. In 1950, the larger railroads operated some 147,511 passenger route miles. By 1968, that fell to 58,130. Operating losses were huge. On the famed California Zephyr domeliner service between Chicago and San Francisco losses, rose to $2.6 million in 1969 on just the Western Pacific portion (with reasonably full passenger loadings). The Seaboard Coastline alone had $12 million dollars of out-of-pocket losses relating to passenger service in 1967.

The real problem was high labor costs for railroads and dwindling ridership from cheaper or faster alternatives. But even when the trains were full, they lost money. In short, one wonders how private passenger trains hung on as long as they did.

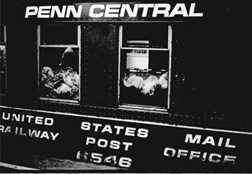

The answer is the United States government. The U.S. Post Office paid to have pre-sorted mail move in high-speed express cars on the head end of passenger trains. Railway Post Office (RPO) cars also carried mail workers who sorted en route, dropping off and picking up mailbags on the fly. This amounted to millions in revenue for the railroads and that helped offset (but not eliminate) passenger losses. Most railroads continued quality passenger service primarily as public relations. Great Northern Railway President John Budd said it best in TRAINS magazine in 1969 when he noted, " The world judges the railways by their passenger service. If this is the window through which we are viewed, we must wash it and shine it, or cover it with a dark shade."

But real trouble for passenger trains arrived around 1966, when the US Post Office introduced a harmless little mail expediter – the Zip Code. The Zip Code would lead to more pre-sorted mail and suburban sorting centers. Instead of sorting your mail at the local office and forwarding out-of-town mail to the downtown branch, all mail would be moved to a central sorting station outside of town (and not adjacent to a railway). Local mail would be returned and out-of-town mail would be either trucked or flown to destination. The large central downtown post offices next to the railway stations were closed as sorting centers. Airmail stopped costing extra.

Suddenly, the railroad passenger trains were bereft of their head end revenue and the losses became staggering. However, in order to eliminate a passenger train, a railroad would have to apply to a government agency, the Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC), for approval. This became a hot-button political issue, as people, even those who didn’t ride the train, didn’t want to lose their rail service. The ICC train-off petition became difficult to achieve and the losses continued.

In part, this led to the largest rail bankruptcy of all time – the Penn Central, which ran about 35 percent of passenger trains in America (by frequency). The government then turned to the Department of Transportation for a solution. In 1971, they came up with a short-term fix, originally called Railpax, and formally known as the National Railroad Passenger Corporation (NRPC).

Here’s how it worked: The railroad could join and buy shares of the NRPC by paying its 1969 full year out-of-pocket passenger loss. In turn, the NRPC would relieve the railroad from operating all passenger trains without ICC petitions and would pay a fixed access fee if it decided to operate passenger trains over that railroad’s lines. Later, NRPC would decide which passenger cars and engines it would buy from the contributing railroads. The government would throw in $40 million (for its shares) and fund the losses (if any) until 1975 when the whole thing would be re-evaluated. In short, what the railroads were not allowed to do to save themselves, the government could do in the name of saving passenger trains. The fact that another branch of government accelerated this mess just adds to the irony.

Railroads not electing to join had to run their passenger trains until 1973 and after that would face the ICC for any train-off petitions. All but a handful of railroads joined. The exceptions were interesting. Tiny Denver and Rio Grande Western was irked because its large competitor, Union Pacific, was not going to have its parallel mainline clogged with any passenger trains, so they decided to continue on their own schedules, forcing NRPC to move a train on the UP. Nearly bankrupt Rock Island couldn’t afford the entrance fee so they waived. The Georgia Road was afraid of losing its unusual tax-exempt status so they passed. Maverick Southern Railway figured that the new service would be so horrible that it would get kudos for running a superior service (they did) and besides, maybe more people would ride (they didn’t).

On May 1, 1971, the government sort of nationalized rail passenger service. In the course, they changed the name from Railpax to Amtrak. Secretary of Transportation John Volpe, in answer to critics who said it would never make money, noted that if his department didn’t think it would work, they wouldn’t be working so hard to save it. Volpe went on to say (in a prediction he likely regretted), "It (Public Law 91-518) lays the foundation for what in my opinion is destined to be the all-time comeback in the history of American transportation." And that set the tone for Amtrak. It was always intended to be a for-profit organization, but profits proved elusive.

By 1973, Amtrak was not doing well (if you consider $100 million in losses as not doing well). It had trimmed the national rail map to a bare minimum (16 routes) only to find that politicians made them restore some services to another 5 routes (West Virginia, Buffalo–Chicago, Seattle–San Diego, Los Angeles–New Orleans, Norfolk–Cincinnati). But even with the additions, the national passenger map was shorn of lots of service. For example, 113 million passengers were carried in 1966 and just 45 million in 1972.

Fast forward to the Reagan Administration, where every year after his first year in office the President proposed a $0 budget for Amtrak (to get rid of it) and every year maverick Amtrak President W. Graham Claytor, Jr. would storm Capitol Hill and round up enough cash to keep it running. Interestingly enough, it was under the Democrat’s (Clinton) Administration that the fiction of Amtrak’s profitability resurfaced. Amtrak was told it could have its budget if it promised profitability by 2001. So they dutifully promised and the government would almost provide what was asked, but always cut the budget.

In this way, Volpe’s fiction was maintained. The goal of profitability was just around the corner (in 2001). And when 2001 arrived, the GAO found that Amtrak had mortgaged Penn Station, owed millions and had a capital spending need to keep even minimum service going and no money to spend. Amtrak’s President Warrington resigned and its survival became a real concern. The new president, David Gunn, a maverick in his own right, has made changes and shown no fear of going toe to toe with anyone. When Congress threatened not to fill his admittedly minimalist budget, he said that since he couldn’t tell which parts of Amtrak Congress didn’t want to operate, he would just shut the whole stinking thing down. And he nearly did, but the DOT and Congress blinked and found enough money to keep it going.

So right now, Amtrak is looking hard at its loss leaders, Congress is considering making the states contribute for service–who knows what is in the works? Maybe a move towards overnight service operated like cruise trains, similar to Australia’s Indian Pacific. That service is privately operated and runs twice to three times a week across the continent, connecting the Indian Ocean with the Pacific. And it makes money. It’s also bloody expensive. So you can figure that on the block are long distance trains such as the Zephyr between Chicago and San Francisco, most of the overnight trains, and some corridor services.

If you were considering a long distance train ride, this summer might be a good time. The scenery between Sacramento and Denver is spectacular. Cuesta Grade outside of San Louis Obispo and the coast running down to Los Angeles is phenomenal. The northern route between Seattle and Chicago is the easiest introduction to the rugged parts of the northern states. Better do it soon, though.