The story of the ‘O’

By Susan Pultz Williams

Published: April, 2005

Next time you lift a finely-fluted oyster shell to your lips and slurp down the plump cold meat that tastes something like the sea on a fresh clear day, consider this: you’re not just eating a rich appetizer—you’re taking part in a timeless dining ritual. You’re enjoying what native Californians enjoyed in ancient times, what the gold miners prized after a hard days work, what Jack London wrote stories about, and what food connoisseurs in California and around the world continue to crave. Passion for oysters is as old as the hills surrounding San Francisco and Tomales Bays, hills that have seen oysters come and go for thousands of years.

In prehistoric times, oysters thrived in the Bay and were a diet staple of the Ohlone and Coast Miwok, who lived in small villages beside the Bay’s creeks, streams, and tidal wetlands. The mounds of shells that they left behind, mostly oyster, mussel, and bentnose clam shells, provide evidence that these native Californians enjoyed an abundant shellfish population for many millennia. Seventeenth-century Spanish explorers found shell mounds, also called “middens,” as long as football fields and as tall as 2- or 3-story buildings. Studies of the middens and of ancient shell reefs long buried under Bay sediment suggest that the oyster population peaked more than 2,000 years ago.

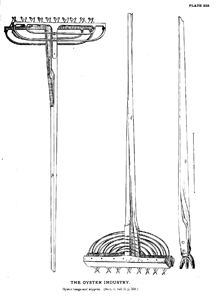

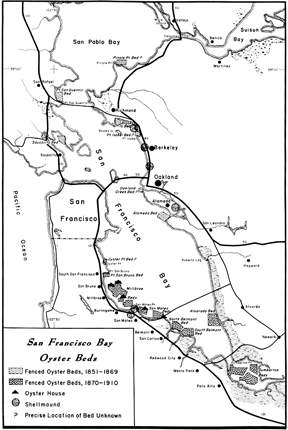

We don’t know how the Bay’s native oysters, Ostrea lurida, fared after that, but we do know they were rediscovered by immigrants drawn to the Bay Area by the Gold Rush. In the early Gold Rush days, miners paid $20 a plate for Bay oysters, but were soon passing them up in favor of John Stillwell Morgan’s imports from Shoalwater Bay (now Willapa Bay) in Washington State. Called Olympias, or Olys, the imports were the same species, but larger, tastier, and more abundant. Soon oystermen began to store and grow Olys in artificial beds along Sausalito’s shoreline. Underwater fences kept out aquatic predators, but could not hold back the tons of silt and mud washed down to the Bay by hydraulic mining operations in the Sierra Nevada. To avoid the silt, Morgan and other oystermen moved their beds to Millbrae and the South Bay.

Then, after the transcontinental railroad was complete in 1869, oystermen began shipping East Coast oysters in from New York. Packed in wooden barrels with plenty of ice, the dime-sized Crassostrea virginica arrived at the Bay to be fattened up in the artificial beds, and soon became more popular than the Olys. Demand for the eastern “sea fruit” grew and reached a peak in the ’90s when more than 250 train car loads of oyster seed were shipped in and 2.7 million pounds of mature oysters were harvested.

During these years, the heyday of commercial oyster production in the Bay, hundreds of acres of San Mateo County’s tidal mudflats were virtually paved with oysters. Oyster pirates like Jack London, roving in gangs, snuck into the commercial beds at night and stole small boatloads of oysters. Then later, as London describes in his short story from 1905, “A Raid on the Oyster Pirates,” he joined the side of the law and helped bust the poachers.

Around the turn of the century, the Bay-grown eastern oysters began to fail, the victims of raw sewage and industrial pollution; they were blamed for several typhoid outbreaks. As production dwindled and public suspicion mounted, oystermen moved their beds to other west coast bays. Untouched by industrial contamination, Tomales Bay, a narrow, 22-mile-long inlet located 50 miles northwest of San Francisco, became a preferred oyster growing spot. Oyster production in San Francisco Bay stopped completely by 1939, but continued to expand in Tomales Bay, where the industry still thrives.

A few oyster companies have settled in Tomales Bay, now a National Marine Sanctuary, because it offers the clean, cold water, abundant phytoplankton blooms and tidal action necessary for growing rich-tasting oysters with beautiful shells. Among these aquaculturalists, the Hog Island Oyster Company started up in 1982 and now sells more than 3 million oysters each year to fine restaurants around the country. Hog Island grows four types of oysters, all of them imports: the Pacific (also known as the Japanese oyster), Eastern, European, and Kumamoto. (See inset.)

But in San Francisco Bay, oysters are scarce. Siltation and contaminants continue to threaten the native Olympia oysters (Ostrea lurida), as well as the entire ecosystem; the more than 200 invasive non-native species living in the Bay include exotics that prey on oysters, crowd them out or consume their food supplies.

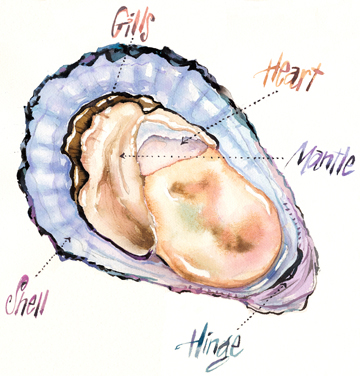

For the past few years, biologists have been trying to figure out how to help oysters make a comeback in the Bay. But what’s driving their interest is not the commercial value of oysters: it’s that oyster reefs would help boost biodiversity in the Bay by providing habitat for small fish and invertebrates, which, in turn, would be appetizing to larger fish and birds. It’s also that these mollusks filter as much as 25 gallons of water a day—either trapping sediment and pollutants in their bodies or forming them into packets which they discharge onto the bottom—meaning that a substantial oyster population could improve the Bay’s water quality.

Restoration projects in the Chesapeake Bay, begun in the mid-1990s, have demonstrated that oyster populations can be turned around. Until a few years ago, however, Bay Area biologists wondered if the native Olympia oysters still lived in the Bay in areas that could be reached easily by researchers and volunteers who might work on restoration. Then in 2001, Save the Bay staff and volunteers dropped “oyster necklaces,” strings with oyster shells tied on, into the Bay at several locations to see if tiny oyster larvae would attach themselves to the shells and start to grow. They did. Oysters were found at Coyote Point, in Richardson Bay, and in Sausal Creek, next to an urban area.

Inspired by these findings, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Fisheries, with funding from local foundations, started two pilot restoration projects: one in Tomales Bay started in 2003 and the other began in Richardson Bay in 2004. Their approach has been to place mesh bags filled with oyster shells, weighing about 200 lbs. each, into shallow warm water where oysters like to live. Biologist Mike McGowan, who is leading the Richardson Bay project, explains that any oyster larvae that may be drifting around need to settle on hard surfaces—like the shells or reefs that have mostly disappeared along with the oysters—in order to grow; otherwise, they just die or get eaten.

While native oysters have not turned up on the experimental reefs in Tomales Bay, early results for Richardson Bay have been encouraging says McGowan. In February, his team found dense colonies and the oysters are large and mature enough to spawn this spring. With another grant from NOAA, McGowan and Michele Pearson of Tiburon Audubon will expand the restoration project in Richardson Bay. Pearson is optimistic. She says, “Oysters won’t save the Bay, but they’re an important piece of the puzzle.” McGowan hopes that someday he’ll be able to pull an Olympia oyster straight out of the Bay and slurp it down just like the Ohlone did so long ago.

Parts of this article are based on an article first published in ESTUARY, a bimonthly publication dedicated to providing an independent news source on Bay-Delta water issues, estuarine restoration efforts and implementation of the S.F. Estuary Project’s Comprehensive Conservation and Management Plan (CCMP). It seeks to represent the many voices and viewpoints that contributed to the CCMP’s development. ESTUARY is funded by individual and organizational subscriptions and by grants from diverse state and federal government agencies and local interest groups. Administrative services are provided by the S.F. Estuary Project and Friends of the S.F. Estuary, a nonprofit corporation. Views expressed may not necessarily reflect those of staff, advisors, or committee members.